This section contains historical images that may reveal plot elements from later in the book. If you’ve already finished The Reservoir, read on. If you haven’t, be warned! New images will be revealed regularly.

A brief story appeared in the Richmond Dispatch the day after the discovery of the body. Tommie saw it and hoped there would be no further headlines.

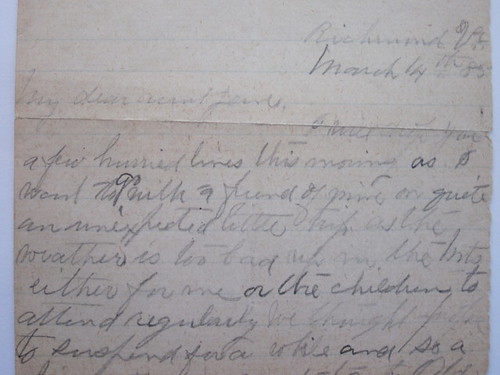

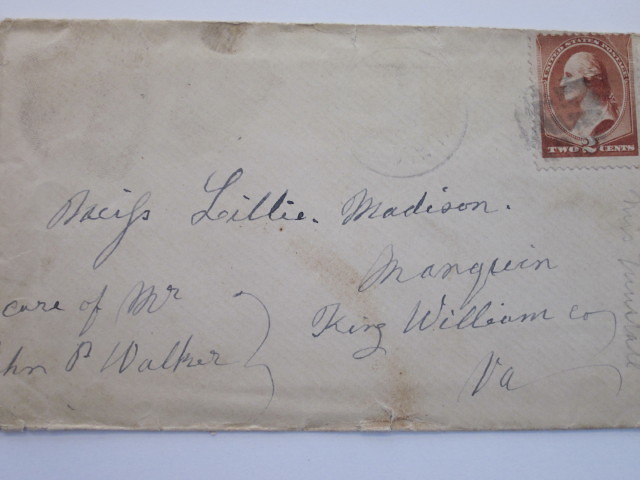

The only extant piece of writing in Tommie’s hand, this letter to Lillie was torn at some unknown time. He apologizes for not visiting her and suggests she should marry a “fellow” she was apparently interested in. He expresses eagerness to hear from her and signs off, “Your fond friend T. J. Cluverius.” No other letters from Tommie to Lillie were ever found.

Not long before her fateful trip to Richmond, Lillie asked Aunt Jane to lend her five dollars, no doubt for traveling expenses, rather than winter clothes.

Lillie reputedly received this letter, ambiguously dated “March 1885,” from a friend requesting that she come help care for the friend’s aunt. The prosecution argued that the letter was a ruse, concocted by Lillie and Tommie as an excuse to meet in Richmond. In the novel, we see them working on this letter together.

In a hastily penciled letter to Aunt Jane, Lillie says she is going to visit a friend at Old Point Comfort, a resort at Fort Monroe at the mouth of the James. She dated it the day after she disappeared, and signed it “I remain always your loving & devoted Lillie.” Her mental distress can only be imagined.

Lillie’s trunk held many empty envelopes addressed to her. The prosecution suggested that she destroyed letters to hide evidence of her relationship with Tommie. The defense argued that such a suggestion subverted the old maxim “that which does not exist shall be held never to have existed.”

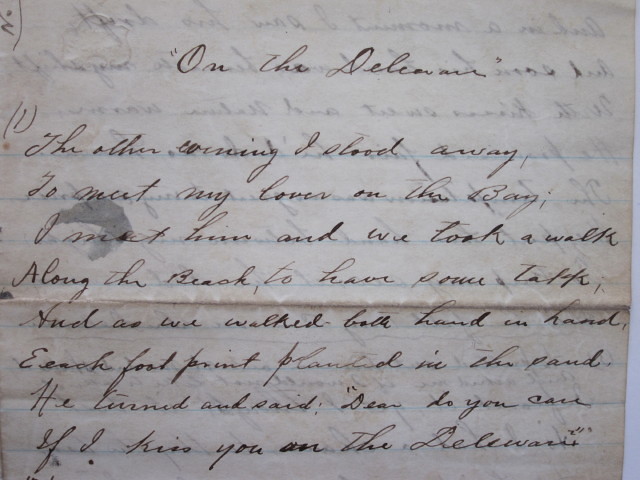

The “dirty poem” was discovered under the lining of Lillie’s trunk. It was unsigned, but the prosecution claimed it was in Tommie’s hand. The poem gets bawdier and cruder as it continues: “He began to blow and grunt, And finally pressed it up my . . .” and so on.

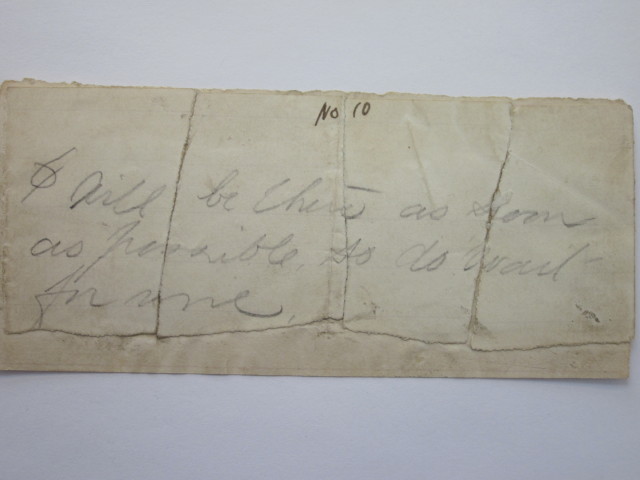

This torn note was a crucial piece of evidence. It was reportedly found in a trashcan at the American hotel, inside an envelope addressed to Tommie.